Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Types of Farming

- Farming in the Hills

- Salt Farming

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Traditionally Grown varieties of Rice

- Sweet Rice: Cultivation and Varieties

- Salt Rice: Cultivation and Varieties

- Rice Husking Traditions

- Use of Technology

- Contributions of Agri-Tech startups

- Hydroponics in Thane

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Issues Caused by Climate Change

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

THANE

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

Thane is a district with a complex, dual identity. While vast parts of the district and its talukas are increasingly becoming industrial hubs, leaving behind their agricultural roots, there are still regions like Vasind that hold on to this once-dominant means of livelihood. The agricultural history of Thane runs deep and is far from ordinary. Its legacy is woven into the fabric of its past, with historical records testifying to its prominence as a center of salt trade and a variety of crops.

For many older and indigenous communities, farming was not just a way of life but the foundation of their identity. However, the ongoing shift towards urbanization has caused a sense of loss and disconnection. This displacement, felt acutely by these communities, is not unique to Thane. Across the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), rapid industrial growth is severing long-established ties of communities to their land. Although farming continues in Thane, with a variety of crops still being cultivated, the future of agriculture in the district remains uncertain as modernization continues to reshape the landscape.

Crop Cultivation

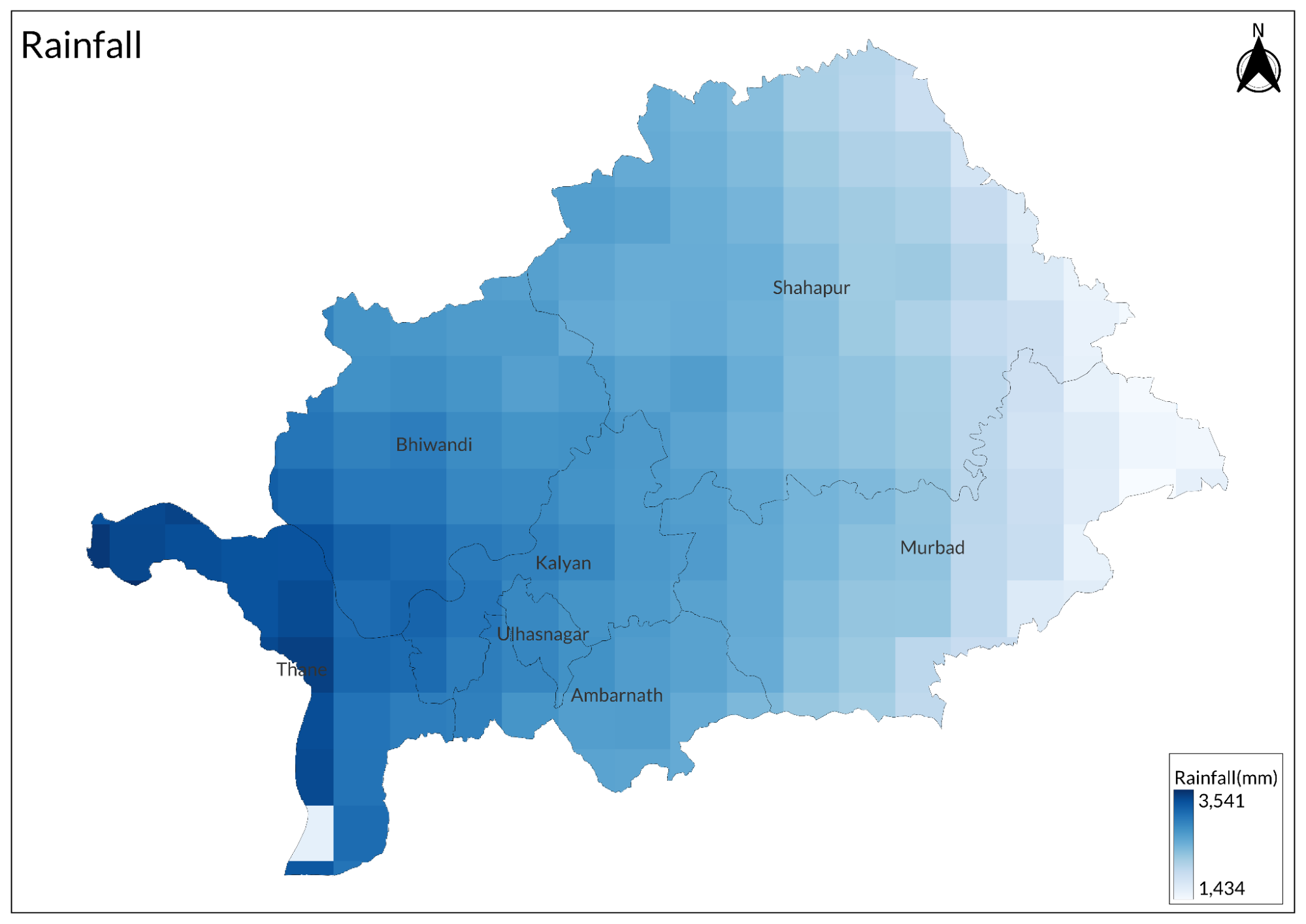

Thane lies in the Western Ghats and Coastal Plains region of Maharashtra and has a hot-humid climate. It has long been a hub for diverse crop cultivation. The district’s agricultural landscape is shaped by its abundant rainfall, making it ideal for growing a variety of crops, both food and horticultural. The district’s primary crop, as per the ICAR’s Agriculture Contingency Plan, is Rice (paddy), which is cultivated mainly during the Kharif season, benefiting from the region's abundant rainfall. Alongside rice, drought-resistant crops such as Nagli (finger millet) and Varai (barnyard millet) are grown, particularly in areas with limited water resources. Other staple crops cultivated in the district include Urad (black gram) and Groundnut (peanut).

Thane’s horticultural production is another major facet of its farming economy. The region is known for its cultivation of Mango, Sapota (chiku), and Cashew, which thrive in the district’s tropical climate. Papaya and Jamuns are also grown here, with the Badlapur Jamun also having a GI tag, which it received in 2024. The fruits contribute to the district’s varied agricultural output, and they are both consumed locally and sold in regional markets.

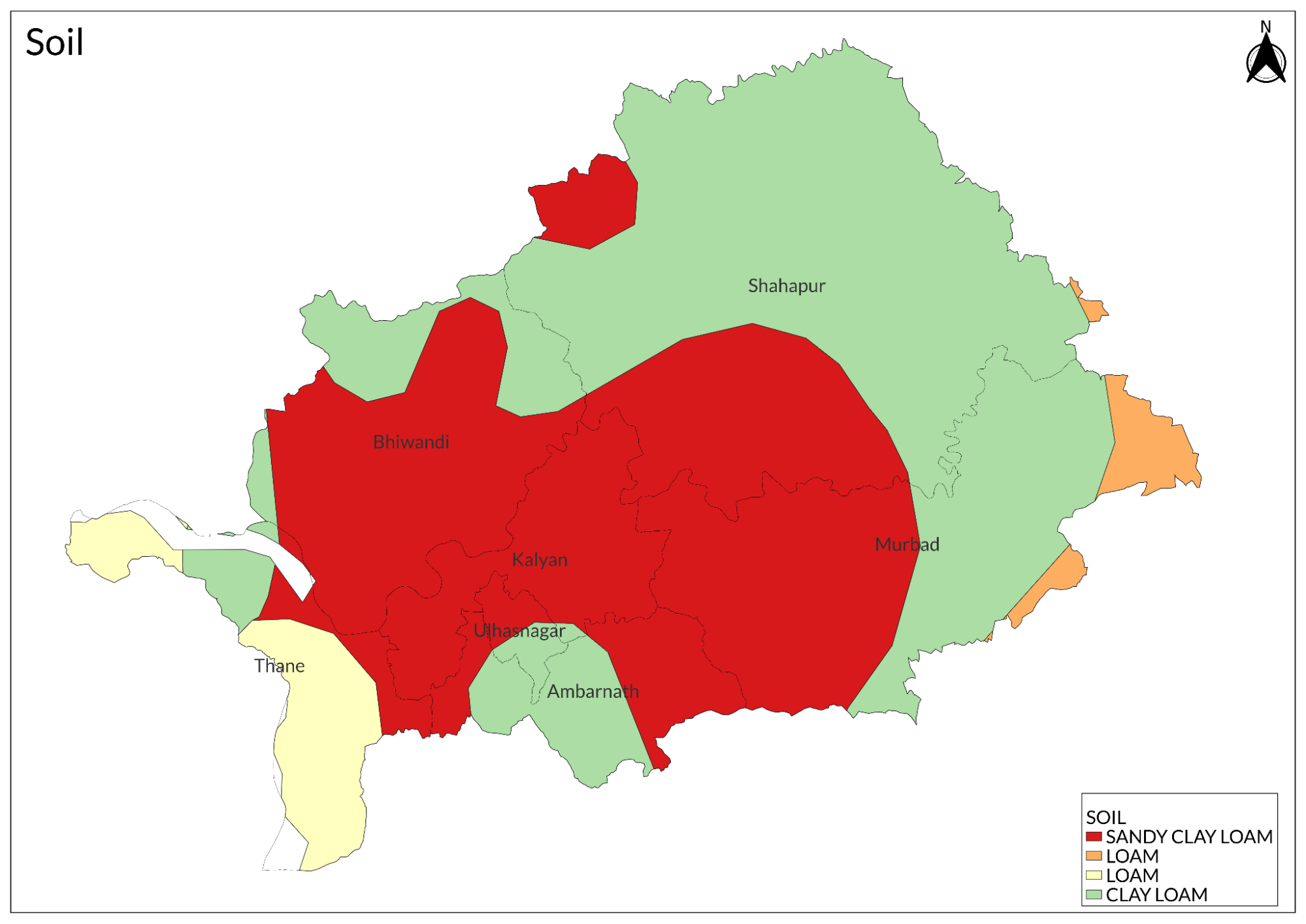

It is said that the region’s diverse soils, which include sandy, red loamy, and laterite types, are particularly conducive to a broad array of crops, from cereals to cash crops. In the past, perhaps the district was home to a far broader range of agricultural produce. As noted in the 19th-century district gazetteer, grain crops like rice, Nachni (finger millet), and Vari (barnyard millet) were dominant, but the region also saw the cultivation of a wide array of other crops.

Pulses such as Black gram, Tur, and Gram, along with oilseeds like Gingelly (Sesame) and Castor, were integral to the local agricultural economy. Fiber crops such as Bombay hemp (Crotalaria juncea) and Ambadi (Hibiscus cannabinus), along with miscellaneous crops like Sugarcane, Chillies, and Ginger, were also actively grown.

Additionally, salt production has long been a key feature of Thane’s agricultural history, contributing significantly to its economy. This historical variety of crops highlights the once diverse and thriving agricultural landscape of the district.

Agricultural Communities

Farming in Thane district has long been influenced by a diverse range of communities. The district’s agricultural landscape, a mix of coastal and inland regions, is shaped by communities that have worked the land for generations. As noted in the Thane Gazetteer, almost every community in the district participates in some form of agriculture, though certain communities have become particularly renowned for their farming practices.

Kunbis form the backbone of Thane’s farming community. It is noted in the colonial district Gazetteer (1882) that Kunbis are responsible for creating the expansive, embanked rice fields that define the district. While their tools are rudimentary, typically wooden plows, and their farming methods are labor-intensive, the Kunbis’ dedication to rice farming is unwavering. They continue to work in flooded fields during the monsoon season, often up to their knees in water. Their focus is primarily on rice cultivation, with minimal involvement in other forms of agriculture like dairy or vegetable farming.

Other significant agricultural communities include the Agris, particularly those from Salsette, who are known for owning sweet rice land. These communities, along with the Ravs of Murbad, contribute significantly to the rice-growing economy of Thane. However, these farmers often struggle with poverty, which limits their ability to expand their agricultural practices.

The Agris and Son Kolis, who reside along Thane’s coastline, lead a different agricultural lifestyle compared to their inland counterparts. The Gazetteer notes that these coastal farmers practice salt rice cultivation, a form of farming that requires minimal labor and yields good profits due to the high prices their salt and wood bring. This makes them financially more stable compared to the inland Kunbis, who face more labor-intensive farming conditions.

Despite the diversity in farming communities, there have been a few troubling trends in recent years, such as the disappearance of small landholders and land being taken by authorities for urbanization and industrialization, which have adversely affected agriculture in the district. The Gazetteer also mentions how the existence of a debt trap has historically affected farmers in the district, especially smaller marginal farmers. These farmers are extremely reliant on moneylenders, which leaves them vulnerable. The moneylenders, on the contrary, are also large landowners and have unsurprisingly increased their wealth. These wealthy landholders often have tenants working their fields, with the crop yield split between the landowner and the tenant, usually in a ratio of half or one-third, depending on the quality of the land.

This evolving landscape reflects the challenges faced by Thane’s agricultural communities, with many struggling to maintain traditional farming practices in an increasingly difficult economic environment.

Types of Farming

According to the colonial District Gazetteer (1884), the main division of soils in the region was described as “sweet” and “salt.” Sweet land could be either black or red: black soil, known locally as shet, refers to the plain rice fields, while red soil, called mal varkas, is found on the flat tops and slopes of trap hills and is used for growing nachni (finger millet), vari (little millet), and other coarse hill grains.

Rice lands were further divided into two main types: bandhni and malkhandi. Bandhni lands are either banked fields that can be flooded or low-lying fields without embankments where rainwater naturally accumulates. These low fields are considered the most productive because the standing water leaves behind a rich layer of fertile deposit. Once the water is drained or evaporates, the land is ploughed and typically planted with gram or other late-season crops. Little extra labour is needed, as the weeds and grasses killed by the standing water decompose and enrich the soil. Malkhandi lands, in contrast, are open fields where no water collects and which have no embankments.

Farming in the Hills

The district of Thane lies in the Western Ghats and Coastal Plains region, which is the northernmost part of the Konkan lowlands. It comprises the wide Ulhas basin on the south and the hilly Vaitarna valley on the north, together with plateaus and the slopes of the Sahyadri. From the steep slopes of the Sahyadri in the east, the land falls through a succession of plateaus in the north and center of the district to the Ulhas valley in the south. These lowlands are separated from the coast by a fairly well-defined, narrow ridge of hills that runs north-south to the east of Thane Creek, parallel to the sea. A few isolated hills and spurs dot the district area as well.

The tillage of the Thana Hill indigenous communities is, or rather was, the forest clearing system that is locally called dahli. Under this system, one who paid a certain amount might clear a space in the forest, cut and burn the trees and bushes, and raise a crop of Nachni. Without any ploughing, the seed was cast in the ashes, and the grain was left to grow and ripen uncared for. However, this practice has long been discouraged and is now suppressed.

At present, such Warlis, Thakurs, and Malhari Kolis are settled in villages and own rice land, cultivated in the same way as Kunbis. Those who neither own nor rent rice land, but cultivate upland, or varkas, raise crops of Nagli or Nachni and Vari or Dhanorya. They are known to rent the plow and bullocks of the Kunbis or prepare the ground with hoes and manual labor.

A very different form of tillage is occasionally carried on by Warlis and Raikaris. A rough terrace is made on a riverbank, and the soil is turned with the hoe, manured with cow dung, sown with such vegetables as Kali vangi, Vel vangi (varieties of Eggplant), and Red pepper, and in the fair season watered by hand from the river. The Raikari community is known to build a hut near their farms and to carry out two occupations, one fishing and the other gardening.

Salt Farming

The earliest mention of Thane was seen in the works of the Greek philosopher, Ptolemy (367 BCE - 283 BCE), who referred to a place, Chersonesus, which is believed to be a place around Thane Creek. Early explorers and chroniclers such as the 10th-century Arab geographers Al Masudi and Ibn Hawqal, and later on the 13th-century Venetian Merchant-explorer Marco Polo, have described that the trade of Food articles, Rice grew in the Konkan region, Brown Incense sticks, etc, was carried out through Thane. These articles were sent to Arabian and African ports.

Likewise, people such as H.M. Elliot and Marco Polo have mentioned Salt Farming in their respective books. Ferishta, a 15-16th century historian mentions that salt made in the Thana creeks was sent inland to Devgiri and other Deccan centers; Coconuts, mangoes, lemons, and betel nuts, and leaves grown in Thane were also probably being sent inland and by sea to Sindh, the Persian Gulf, and the Arabian coast; This gives us a much needed historical background regarding the items that were being produced in Thane.

Salt, still to this day, is an important source of income for many. The land on which Salt is produced is locally known as Khar Land (saline land). Before salt reaches the consumer market in neatly packaged forms bearing various brand names, it undergoes a fascinating, long, and toilsome journey, being cultivated and harvested from salt farms. In a 1983 article, Coomi Kapoor talks about how salt pans can sometimes damage grazing and arable land, negatively affecting the local economy and ecology, if proper precaution isn’t taken.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

The district is known for its rich history of rice cultivation, has developed a process of rice farming that remains largely traditional.

Traditionally Grown varieties of Rice

There are two types of rice grown in the district, locally known as Sweet and Salty Rice. These further have divisions among them.

Sweet Rice: Cultivation and Varieties

Traditionally, the first step is to manure the field or nursery plot where seeds will be sown. In upland plots (varkas), a sloped area near the field is used. Manuring often begins in March or April by burning piles of cow dung, branches, or grass, covered with soil to keep the ashes from blowing away, a practice rooted in local folklore.

By this time, earthen mounds and bandhs around fields are repaired using an iron bar called a Pahar. When the monsoon arrives in June, seeds are sown and the seedbed is lightly ploughed and harrowed, unless heavy early rain makes the soil too muddy, in which case ploughing is done first.

After 18–20 days, seedlings are ready to be transplanted in bunches (Chud) spaced about a foot apart. The crop matures between June and October and is harvested with a sickle (Vila). The stalks are tied into sheaves (Bhara), carried to the Khale (threshing floor), and piled into Udvas.

Threshing involves beating the grain on the ground, then trampling by buffaloes tied to a central pole (Kudmad). Empty grains are separated by winnowing. Sometimes, sheaves are struck against a wooden block instead of trampling to preserve straw for thatching, though this can waste some grain.

At home, the outer husk is removed with a Jate (grindstone). The rice (Tandul) is then further cleaned with a Musal (pestle) and pit on the house floor to remove the inner husk (Konda). In towns like Bhiwandi and Kalyan, this process used to employ large groups of workers using a Musal and Ukhali (wooden mortar).

Sweet Rice is further divided into Halva, which needs less water and ripens by October, and Garva, which needs more water and ripens by November.

- Halva varieties include Kudai, Torna, Salva, and Velchi.

- Other early types are Mhadi, Halva Ghudva, and Patni Halvi.

- Garva varieties include Garva Ghudya, Dodka, Garvel, Ambemohor, Dangi, Bodke, Tambesal, Ghosalvel, and Kachora.

Salt Rice: Cultivation and Varieties

The tillage of Salt Rice is different. The land is not ploughed or manured with ashes. Seeds are broadcast on mud or water and left to sink by weight; seedlings are never transplanted. Salt Rice ripens in November and must be protected from saltwater. Its straw is burned for ash manure rather than used as fodder. The grain, which is red, is mostly consumed locally by poorer households. Munda and Kusa are the main Salt Rice types.

Rice Husking Traditions

Rice husking was once an important trade in this region, especially in Kalyan, as noted in the Gazetteer (1884). Unhusked rice arrived from nearby areas. Women ground it by hand to remove outer husks, winnowed it, and used wooden mortars and iron-bound pestles to pound out the inner husk. The rice was classified by how many times it was pounded: once (Eksadi), twice (Dusadi), or three times (Kalhai). A large share was sent to Mumbai

Use of Technology

The use of modern technology in Agriculture has increased in the past few decades. According to NABARD’s Potential Linked Credit Plan of 2023-24, the district has 351 agricultural Tractors, 1436 power Tillers, and 3520 Threshers and Cutters.

Contributions of Agri-Tech startups

Several agri-tech startups are active in the Thane district, focusing on improving storage, mechanisation, and alternative cultivation methods. One such initiative is the development of the “Subjee Cooler,” a low-cost cooling unit that allows farmers to store unsold produce for four to six days, helping them reduce waste and sell at better prices. The innovation was launched by RuKart Technologies, founded in 2019 by IIT Bombay alumni. Supported by seed funding and guidance from CTARA, IIT Bombay, the startup aimed to deliver over 150 units in its early phase.

Electric tractors are also being introduced as part of efforts to modernise farming practices. A locally developed electric tractor uses an advanced electric powertrain and self-driving technology. It is expected to help farmers reduce fuel costs and support environmentally sustainable agriculture.

Hydroponics in Thane

Hydroponic farming has gained ground as an alternative to traditional soil-based cultivation. In Thane, Prashant Joshi (2021) mentions that one of the largest hydroponics farms covers about 10,000 square feet, producing a variety of green leafy vegetables and fruits year-round using clean, filtered water and a sterile, sealed growing system. The produce is supplied across urban and suburban parts of the district, and farm-gate sales and “salad boxes” cater to health-conscious consumers.

Institutional Infrastructure

According to the NABARD’s 2023-24 Potential Linked Credit Plan for Thane, the district has an average developed agricultural infrastructure, which includes 5 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), 22 godowns, 69 cold storages, 4 soil testing centers, and approximately 223 fertilizer, seed, and pesticide outlets. There is also one Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) supporting agricultural extension services in the region. In addition to this, there are 12 commercial banks, 1 Regional rural bank and District Central Cooperative bank,11 branches of Maharashtra Gramin Bank, 67 branches of Thane DCCB, and 210 Primary Agricultural. Cooperative Societies.

Market Structure: APMCs

There are APMCs at Bhiwandi, Murbad, Kalyan, Shahpur, Uand lhasnagar. The APMC at Kalyan is the oldest one. Paddy, Nagli, Ladies Finger, Wheat, Coconut, Tomato, Mango, Green Vegetables, etc are important commodities that are sold at these markets.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

No. of Godowns |

|

1. |

Bhiwandi |

1958 |

Sachin Balaram Patil |

6 |

|

2. |

Murbad |

1958 |

Laxman Dattatray Sarninge |

1 |

|

3. |

Kalyan |

1957 |

Kapil Vishnu Thale |

NA |

|

4. |

Shahpur |

1958 |

Nandlal Daulat Dohle |

2 |

|

5. |

Ulhasnagar |

1994 |

Ujjwal Vithhalrao Deshmukh |

NA |

Farmers Issues

Issues Caused by Climate Change

Farmers in Thane face significant challenges due to erratic rainfall and water scarcity. In some hamlets of Shahapur taluka, it has been reported that insufficient rainfall during the sowing season has led to crop losses, while excessive rainfall in later months has caused flooding and damage to paddy fields. Although Thane district is drained by the Ulhas and Vaitarna rivers and benefits from several major dams, much of the water stored in Bhatsa, Modak Sagar, Tansa, and Upper Vaitarna is diverted to supply urban areas, leaving local farming heavily dependent on monsoon rains.

Seasonal water shortages from December to May often lead to reliance on tankers for drinking water. Many from Scheduled Tribe communities are especially noted to migrate for seasonal work in brick kilns or sugarcane fields in other parts of Maharashtra and Gujarat, returning in time for the kharif sowing season.

Climate change and inconsistent rainfall continue to affect yields, household food security, and incomes, reflecting broader shifts observed across the region.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Anju Ann Mathew. 2020.This agritech startup helps farmers store produce and sell at a better price.YourStory..https://yourstory.com/socialstory/2020/07/ru…

Coomi Kapoor.1983.Farmers in coastal districts of Thane and Raigad suffer due to salt pans.

Govt. Of Maharashtra. 1882.District Gazetteers, Thana District.Gazetteers Dept. Mumbai.

H.M Elliot.1867.The History of India as Told by Its Own Historians The Muhammadan Period.Cambridge University Press.

https://marathi.latestly.com/lifestyle/health-wellness/agriculture-without-soil-is-happening-in-thane-learn-about-swapnil-shirkes-indiroots-hydroponics-farm-startup-which-produces-clean-and-nutritious-leafy-vegetables-using-only-water-300423.htmlhttps://marathi.latestly.com/lifestyle/healt…

https://ruralindiaonline.org/kn/articles/in-thane-the-rain-has-gone-rogue/https://ruralindiaonline.org/kn/articles/in-…

https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/environment/story/19831031-farmers-in-coastal-districts-of-thane-and-raigad-suffer-due-to-salt-pans-771161-2013-07-16https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/environme…

https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/tender/MAH_Thane.pdfhttps://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/te…

https://www.news18.com/auto/maharashtra-autonxt-launches-indias-first-electric-tractor-in-thane-9022161.htmlhttps://www.news18.com/auto/maharashtra-auto…

ICAR. 2017.MAHARASHTRA Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: THANE.ICAR - CRIDA - NICRA.

Jyoti Shinoli. 2020.In Thane, the rain has gone rogue. RuralIndiaonline.org.

Marco Polo, Rustichello da Pisa.1290.The Travels of Marco Polo.

NABARD. 2023-24.Potential Linked Credit Plan:Thane.Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.

Prashant Joshi. 2021.Agriculture without soil is……using only water. Latestly.

Samreen Pal. 2024.AutoNxt Launches India's First Electric Tractor In Thane. News18.

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.