Contents

- Crop Cultivation

- Agricultural Communities

- Festivals & Rituals Related to Farming

- Types of Farming

- Jowar Cultivation

- Wheat Cultivation

- Orange Farming

- Traditional Agricultural Practices

- Khapli: A Traditional Sowing Method

- Bhuldi: A Technique for Soil Conservation

- Makki ki Roti: A Harvesting Tradition

- Bhooda: Crop Rotation for Soil Health

- Use of Technology

- Maharashtra’s First Female Drone Farmer

- Irrigation Projects

- Institutional Infrastructure

- Market Structure: APMCs

- List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

- Farmers Issues

- Graphs

- Irrigation

- A. No. of Projects

- B. No. of Ponds/Vilage Lakes and Storage Dams

- C. Irrigation Beneficiary Area vs Irrigated Area

- D. Share of Beneficiary Area Irrigated

- E. Tubewells and Pumps Installed In The Year

- F. Irrigation and Water Pumping Facilities

- Cropping Metrics

- A. Share in Total Holdings

- B. Cultivated Area (With Components)

- C. Gross Cropped Area (Irrigated + Unirrigated)

- D. Share of Cropped Area Irrigated

- E. Distribution of Chemical Fertilizers

- Land Use and Credit

- A. Area of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- B. Size Groups' Share in Total Agricultural Land Holdings Area

- C. No. of Agricultural Land Holdings (With Size Group)

- D. Size Groups' Share in Total No. of Agricultural Land Holdings

- E. Agricultural Lending

- F. Agricultural Credit as a share of Total Credit

- Sources

WARDHA

Agriculture

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.

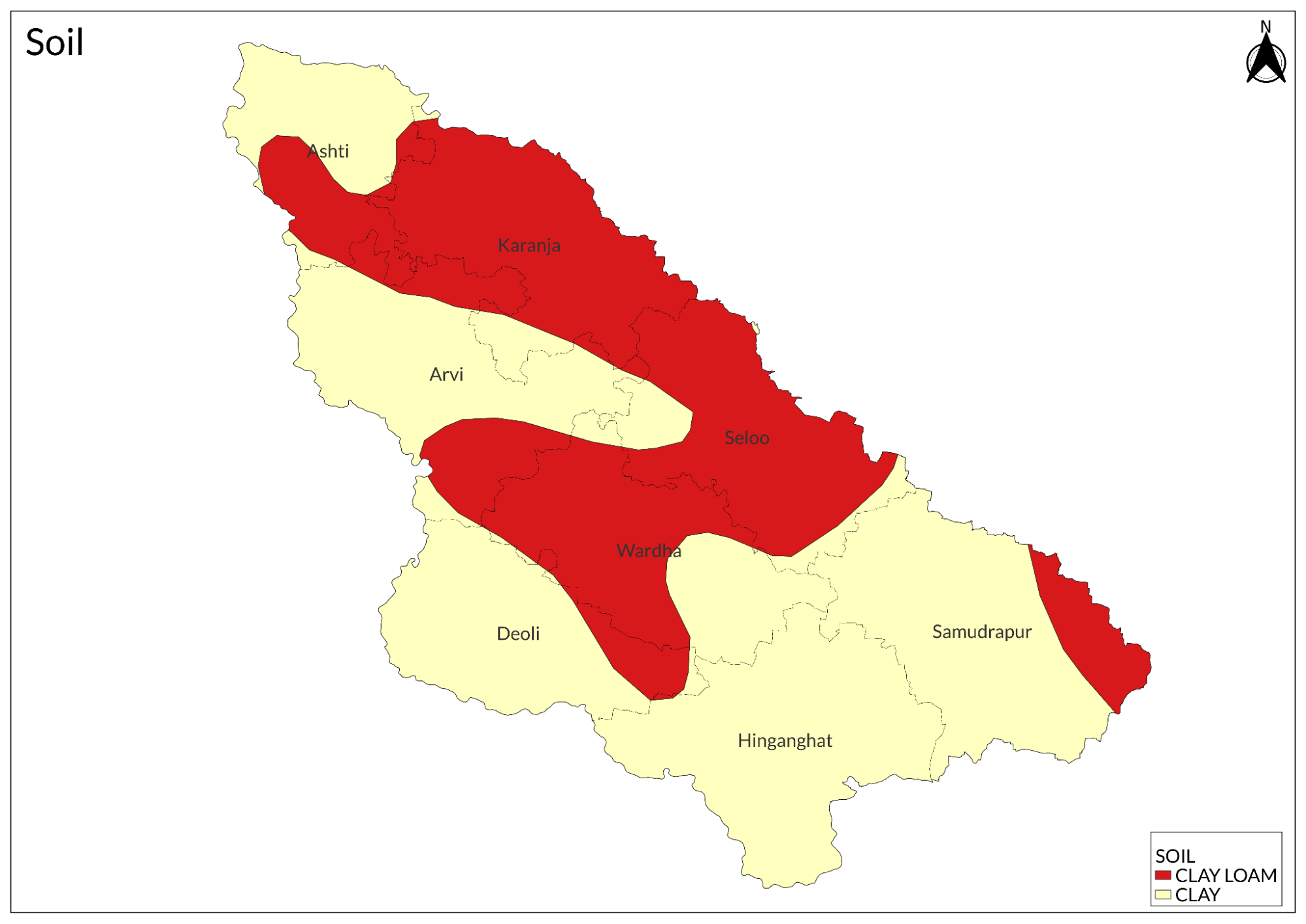

Wardha district, located in the southeastern part of Maharashtra, lies to the west of the Wainganga Valley and is bordered by the Satpura Hills to the north. The district is bordered by the Satpura Hills to the north and the Purna River valley to the west, while the Wardha River flows through its boundaries in the north, west, and south. The region's soil is predominantly composed of fertile medium black and shallow black soils, ideal for a range of crops.

Agriculture plays a vital role in Wardha’s economy and culture. The district covers an area of 6,309 square kilometres, with approximately 4.39 lakh hectares of cultivable land out of a total of 6.29 lakh hectares, according to the NABARD Potential Linked Credit Plan (2023–24). As per the 2011 Census, about 67% of Wardha’s population at that time lived in rural areas, where agriculture remained the main source of livelihood. This close connection to farming is reflected in the district’s diverse cropping patterns and traditional practices, which shape the livelihoods and everyday life of its residents.

Crop Cultivation

The agricultural scene in Wardha is diverse, with crops such as cotton, soybean, and tur leading the Kharif season (monsoon), whole wheat and gram are the dominant crops during the Rabi (winter) season. The district’s cropping intensity, as reported by NABARD, indicates a high level of agricultural activity, with many farmers cultivating multiple crops each year.

According to the district Gazetteer (1974), Wardha has historically supported the cultivation of both food and cash crops. Staples such as jowar, bajra, rice, and wheat have long been central to local diets, while cotton and groundnut have served as the main cash crops. Among Wardha’s notable crops is Waigaon turmeric, a variety grown in Waigaon village. Recognised for its deep mustard-yellow colour, strong aroma, and high curcumin content, Waigaon turmeric has been cultivated for generations and is valued for its quality and health benefits. This variety received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2016, though this registration was only valid till March 2024.

Food in Wardha is closely tied to its farming practices. In earlier times, subsistence farming was prevalent, with families growing a wide variety of crops to meet both their food and economic needs. Interestingly, this diversity in crops is mirrored in the local food culture, with seasonal harvests contributing to the variety of dishes enjoyed throughout the year. Locals often describe how the food they grew was deeply connected to what they ate. This diversity in farming practices was reflected in the variety of dishes served on local tables, as different crops were harvested throughout the year.

Bajra roti, a flatbread made from pearl millet flour, is a staple, often served with dal or vegetables. Similarly, jowar bhakri, made from sorghum flour, is another common dish, highlighting the importance of dryland crops in the region. Sorghum seems to be a crop that is usually used in many dishes in Wardha.

Other regional specialties, such as urad idli (steamed rice cakes made from black gram batter) and rajgira paratha (a flatbread made from amaranth flour), emphasize the significance of legumes and cereals in the district’s agriculture.

Sweet dishes, such as nanari laddu made from nanari flour, ghee, and jaggery, also reflect the agricultural heritage of Wardha. Jaggery, a byproduct of sugarcane cultivation, is a key ingredient in many traditional sweets, linking the district’s agriculture with its culinary traditions.

In Wardha, food and farming are inseparable. The crops grown in the region are not only an economic resource but also a reflection of its agricultural heritage. Each dish tells the story of the land’s farming practices and seasonal rhythms, reinforcing the deep connection between what is grown and what is eaten in the district.

Agricultural Communities

Kunbis form one of the largest farming communities in Wardha district. Sub-groups such as the Tirole, Wandhekar, Khaire, and Dhanoje have long been associated with cultivation and continue to contribute significantly to the local agricultural landscape.

Alongside the Kunbis, communities such as the Telis, Malis, and Marathas also play an important role in agriculture. The Telis are noted for their diligence in farming, while the Malis are recognised for their intensive and organised cultivation methods. Over time, farming in the district has become more inclusive, with groups such as Brahmins, Chambhars, Mahars, and Banias increasingly participating in agricultural activities, as noted in the district Gazetteer (1974).

Alongside these communities, indigenous communities like the Gond and Kamti have also been integral to the agricultural fabric of Wardha. Local farmers point out that members from the Gond community, particularly, practice a form of cultivation known as "Jhum cultivation." This involves clearing forest areas to plant crops such as millets and pulses, a traditional method that has sustained their livelihoods for generations.

Similarly, the Kamti, another community within the district, is known for its expertise in shifting cultivation. This practice, in which they rotate farming locations to maintain soil fertility, is central to their agricultural lifestyle.

Festivals & Rituals Related to Farming

The agricultural festivals and rituals celebrated reflect a deep connection that ties farming with culture and religion. These practices are not just symbolic but are believed to bring real blessings and protection to the fields, ensuring the prosperity of crops.

Akshaya Tritiya, typically observed in May or June, is a festival that holds particular importance for farmers in Wardha. It is considered an auspicious day for starting new ventures, including planting crops. Local farmers view this day as a time to begin the sowing of new crops such as cotton, soybean, and sugarcane, marking the beginning of the new crop cycle.

On this day, farmers perform a ritual planting of saplings, often in fields or farms, to ensure the prosperity of the crops. They believe that beginning the sowing process on Akshaya Tritiya will bring blessings for a good harvest. The word Akshaya means “imperishable” or “eternal,” and farmers see this day as an opportunity to ensure that their crops grow without any hindrance. It is also a time for families to come together, offering prayers for the health of the soil and the well-being of their fields.

Types of Farming

Agricultural practices in Wardha have evolved considerably over the years, driven by advancements in cultivation techniques and the introduction of new varieties. While certain crops that were once dominant have experienced a decline, these changes have been accompanied by innovations that have reshaped the region's agricultural profile. The shift in farming dynamics is particularly evident in the cultivation of jowar, wheat, and oranges, with detailed records of these developments found in the gazetteer.

Jowar Cultivation

Once a dominant crop in Wardha, jowar (sorghum) has seen a significant decline in recent years. As recorded in the gazetteer, jowar was historically the second most important crop in the region, after cotton. It was cultivated both as a staple food and as a key fodder crop, with the stalks, known locally as kadbi, used for cattle feed. Typically sown as a Kharif crop, jowar was also occasionally cultivated in the Rabi season.

The Gazetteer (1974) mentions several traditional local varieties of jowar that were cultivated in Wardha. Ganeri, a variety that was said to be well-suited to fertile soils, and Dukeria, a white variety that was said to thrive in poorer soils, were commonly found in the region. Another variety, Lalpakri, a red jowar, was said to be less susceptible to bird feeding. Perhaps the most intriguing of these was Moti-tura (or Moti-chura), a variety described as having spreading heads that not only deterred birds but also found its place in the preparation of sweetmeats, contributing a distinct local flavor to traditional delicacies.

Over time, many of these traditional varieties appear to have been replaced by high-yielding hybrid varieties, such as Saoner Jowar, CSH-1, and CSH-2. R. Rukmani & M. Manjula (2009) in their study note that over the years, traditional sorghum varieties have been phased out, with only sorghum hybrids now cultivated, making these older varieties a fading memory.

The cultivation of jowar in Wardha followed several traditional methods that were prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as described in the Gazetteer. Land preparation for jowar began with the use of the bakhar (plow), a tool that was also used for other crops. After the initial plowing, the soil was enriched with farmyard manure to prepare it for sowing. Typically, sowing took place in mid-July, with seeds placed in the soil using a tifan (plow). This method, where bamboo tubes were attached to the plow for seed distribution, ensured a uniform spread of seeds.

To maintain soil fertility, it is said that jowar was often intercropped with other crops like moong (green gram), following a traditional ratio of seven parts jowar to one part moong. The shed leaves of moong helped enrich the soil and served as natural manure. Weeding, a vital step in the cultivation process, was carried out with small plows called Daura and dhundia. This process was repeated regularly, especially during the monsoon season, to prevent weeds from competing with the jowar plants.

Wheat Cultivation

Wheat farming has long been a cornerstone of Wardha’s agricultural practices, particularly as a Rabi crop. It is recorded in the district Gazetteer (1974) that the Hinganghat taluka, particularly, with its fertile soils along the Wardha River, was the primary region for wheat cultivation. Historically, the area saw the cultivation of several wheat varieties, including Haura, a hard white wheat, and Hatha, a hard red variety. Another variety, Bansi, though not as widely grown, was prized for its rust resistance, making it a favorite in areas prone to the disease.

Over time, improved wheat varieties began to gain popularity, performing well in both dry and irrigated conditions. The shift to these high-yielding varieties marked an important change in wheat cultivation in the region, with farmers turning to crops that could withstand varying environmental conditions and provide better productivity.

The preparation of land for wheat cultivation involved a detailed process, as recorded in the gazetteer, starting with several ploughings using the baker to loosen the soil, followed by the use of a pathar or log to level the land. Once the soil was properly prepared, farmyard manure and compost were applied to enhance soil fertility. Sowing typically began by mid-October, with the use of a tifan, which was said to be larger and sturdier than those used for other crops like jowar or gram.

Wheat requires regular irrigation, with the first watering given 21 to 30 days after sowing. Subsequent irrigations were applied as needed, based on soil type and weather conditions.

The harvesting process was completed by the end of February or mid-March. The wheat was cut, bundled into sheaves, and threshed manually, marking the culmination of a labor-intensive process that had sustained Wardha’s wheat farming for generations.

Orange Farming

Orange farming in Wardha was another significant agricultural practice, particularly in the region around the Wardha River. The colonial district Gazetteer (1906) highlights that oranges from the district were in high demand, both locally and in distant markets such as Mumbai (in the days when it was called Bombay) and Delhi. While orange cultivation was mainly practiced by affluent farmers due to the initial investment required, it gradually expanded as government initiatives and cooperative efforts made it accessible to a larger number of farmers.

The soil for orange cultivation, as described in the Gazetteer, needed to be well-drained, with black soil being considered the best for this crop. However, loamy soil with lime nodules was also suitable. Farmers typically prepare the land by plowing it deeply during the summer months and then using the bakhar plow for further preparation before planting.

Orange trees were planted in pits that were 3 feet in each dimension, spaced approximately 20 feet apart. The pits were left open to the sun for several weeks before being filled with a mixture of compost and fertilizer. Orange grafts or seedlings were planted between July and September. These trees, once planted, required careful management. Regular irrigation was essential, especially during the fruit-bearing season. However, orange trees took several years to bear fruit, typically producing a first crop after 6-7 years. The trees could continue to bear fruit for 25-30 years, with two harvests per year: one during the Ambia bahar (October to December) and another during the Mrig bahar (February to April). The Mrig bahar crop was considered of superior quality and fetched a higher price in the market.

Despite the promising nature of orange farming, it came with risks. Farmers faced difficulties with pests, such as the light brown caterpillar, which could damage the trees. As a result, determining the suitability of land for orange cultivation was often uncertain, with even experienced farmers unsure whether a particular piece of land would produce a good yield.

Traditional Agricultural Practices

In the Wardha region, traditional agricultural practices have been the cornerstone of farming life for centuries. These methods passed down through generations are deeply intertwined with the culture and knowledge of the local farmers. Among the many techniques practiced when it comes to sowing and soil health, four notable methods stand out, namely Khapli, Bhuldi, Makki ki Roti, and Bhooda.

Khapli: A Traditional Sowing Method

According to local farmers, Khapli is one of the oldest sowing techniques used in Wardha. This traditional method is primarily used by those growing bajra (pearl millet) and jowar (sorghum). In Khapli, seeds are broadcast evenly across the soil surface, without furrowing or drilling, using a traditional tool called khati. Local farmers explain that this method is particularly suited for crops that thrive in dry conditions, as it ensures the seeds are spread evenly, reducing soil disturbance and promoting moisture conservation.

Farmers appreciate Khapli for its simplicity and efficiency. Broadcasting the seeds directly onto the soil minimizes soil erosion and allows for better moisture retention, which is vital in the semi-arid climate of Wardha. Local farmers note that this technique also helps reduce the need for heavy tillage, making it a more sustainable practice that supports soil health over time.

Bhuldi: A Technique for Soil Conservation

Another important traditional practice mentioned by local farmers is Bhuldi, a soil conservation technique that prevents soil erosion, which is a common concern in Wardha's sloped fields. Farmers who grow bajra, jowar, and cholam (sorghum) often rely on Bhuldi, which involves creating raised ridges and furrows across the field. The process, as local farmers say, starts with the soil being leveled first and then raised into ridges and furrows using a traditional implement. This technique helps to slow down water runoff during rains, allowing water to be absorbed into the soil, which is crucial for maintaining soil fertility.

Farmers say that this method not only conserves water but also improves soil structure, making it easier for plant roots to penetrate and grow. According to local farmers, Bhuldi has been passed down through generations, and it continues to be an effective practice for sustaining productivity in the region's fields, especially when faced with heavy rainfall or drought conditions.

Makki ki Roti: A Harvesting Tradition

Makki ki Roti is a traditional harvesting technique used by local farmers, particularly those cultivating bajra and jowar. Local farmers explain that this method involves using a curved blade, known as Makki ki Roti, attached to a long handle, to harvest the mature crops. This technique is especially valued for its efficiency and precision, as it allows farmers to harvest the crop without damaging the plants or leaving behind waste.

Farmers say that the curved shape of the blade helps make clean cuts, ensuring that only the ripe crops are collected. By using Makki ki Roti, local farmers avoid the need for heavy machinery, which could damage the soil or lead to crop losses. According to them, this method reflects the deep respect they have for the crops and the land, as it ensures a careful harvest while also preserving the health of the soil for the next season.

Bhooda: Crop Rotation for Soil Health

According to local farmers, Bhooda is an essential practice for maintaining soil health and preventing the buildup of pests and diseases. This crop rotation method is used to ensure that no single crop is grown on the same land for more than two consecutive seasons. Farmers who cultivate a variety of crops like bajra, jowar, cholam, and moong (mung beans) typically follow a rotation schedule, which helps to enrich the soil and reduce the risk of crop-specific pests.

Farmers explain that after growing bajra or jowar, they rotate in leguminous crops like moong, which help to fix nitrogen in the soil, improving its fertility. This rotation also disrupts the lifecycle of pests and diseases, preventing them from building up in the soil. Local farmers say that Bhooda is not only a practice for soil conservation but also a way to maintain long-term productivity by ensuring that the land remains healthy and capable of supporting diverse crops.

Use of Technology

The use of modern technology in Agriculture has increased in the past few decades. According to NABARD’s Potential Linked Credit Plan of 2023-24, the district has 8120 agricultural Tractors and 117000 Threshers and Cutters. The use of drones in agriculture has also seen a rise in recent years.

Maharashtra’s First Female Drone Farmer

In Wardha, where agriculture remains a primary livelihood, women, like men, play a vital role in farming. Locals often speak of the strong community bonds, with marginal farmers helping each other out on their fields and young girls learning farming skills from an early age. Among these, one woman has stood out, making history in the agricultural landscape of Maharashtra.

A 2024 article published by Krishi Jagran mentions—Linta Shelke, a name now synonymous with innovation in farming, became Maharashtra’s first female drone farmer. Her journey into the drone space began long before the Centre introduced the "Drone Didi Scheme." Shelke, as reported by Krishi Jagran, recalls how her path was anything but easy, balancing her responsibilities as a mother to a three-year-old while stepping outside the confines of traditional household duties. Today, she is recognized as Maharashtra's first female drone pilot and the second in India.

Irrigation Projects

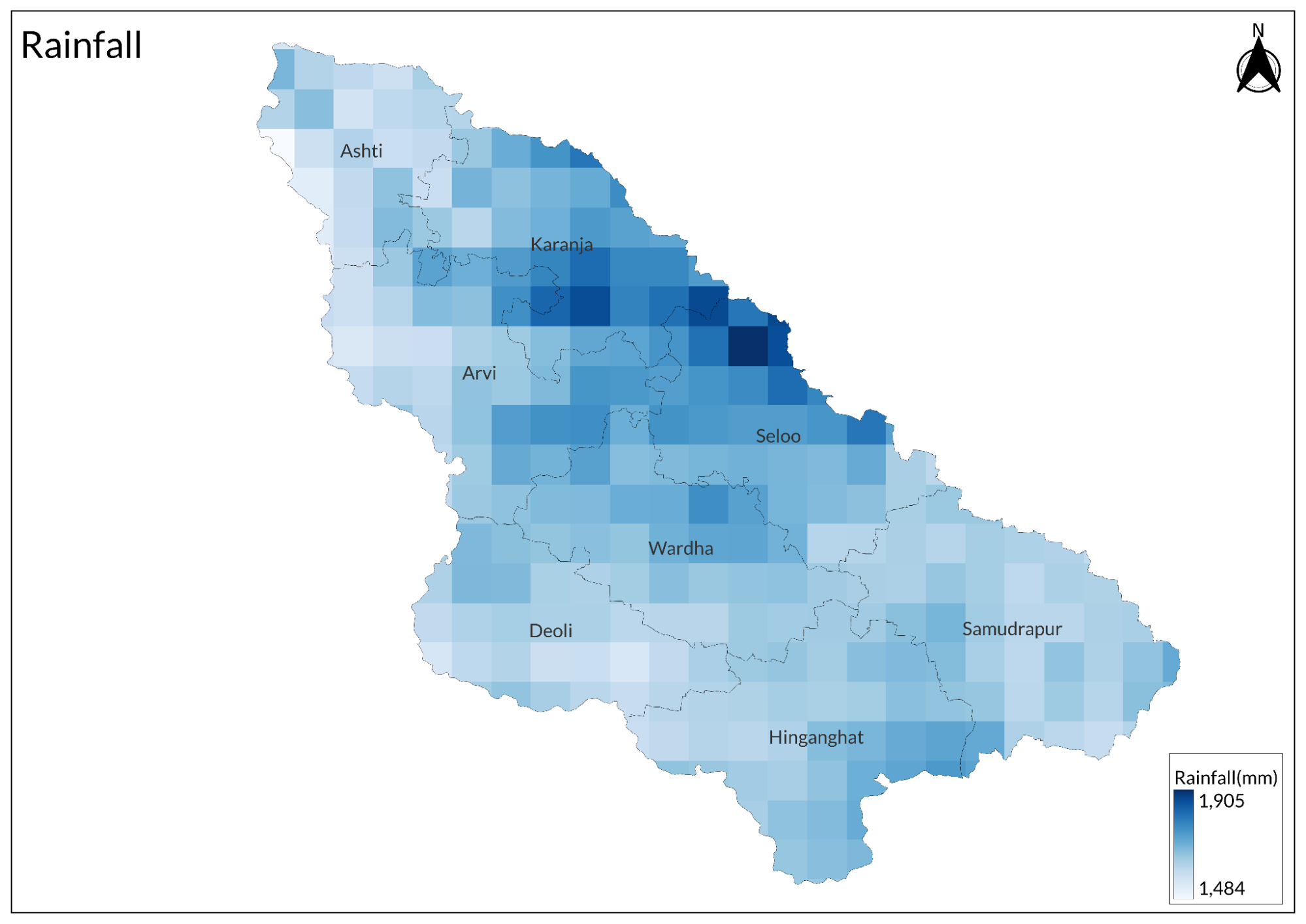

Irrigation plays a critical role in agricultural development, enabling farmers to bring more land under cultivation and grow multiple crops in a year. However, the district of Wardha has faced significant challenges in developing its irrigation systems. The district's non-perennial rivers, which flood only during the monsoon and remain dry for the rest of the year, make canal irrigation unfeasible. As a result, farmers primarily rely on farm-side wells as their main source of water for both agricultural and non-agricultural purposes.

In recent years, the government has made efforts to improve the district’s irrigation infrastructure. In some areas, water is drawn from stream beds using pumping sets or hand pumps. Notable irrigation projects such as the Ashti project (initiated in 1961-62 and completed in March 1967) and the Bor Tank project (started in 1958 and expected to be completed by 1968) have contributed to expanding the area under irrigation.

Additionally, the Vidarbha Watershed Development Project, launched by the Maharashtra government, has targeted 11 villages in Selu taluka and 4 villages in Karanja taluka to implement watershed development activities. The project focuses on measures such as soil and water conservation, farm bunding, building village tanks, constructing check dams and cement plugs, and widening nalas. These efforts aim to enhance water availability and promote sustainable agriculture in the region.

Institutional Infrastructure

According to NABARD’s 2023-24 PLP report, the district has an underdeveloped agricultural infrastructure, which includes 16 Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs), 229 godowns, 2 cold storages, 45 soil testing centers, 187 farmers clubs, 163 plantation nurseries, and approximately 4000 fertilizer, seed, and pesticide outlets. There is also one Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK) supporting agricultural extension services in the region. In addition to this, there are 10 commercial banks, 1 Regional rural bank and District Central Cooperative bank, 06 branches of Vidarbha Konkan Gramin Bank, and 315 Primary Agricultural. Cooperative Societies.

Market Structure: APMCs

The Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) were established to ensure that farmers receive fair prices for their produce. These markets are designed to create a structured environment where farmers can sell their crops to traders, who then bid on them. Once the commodities are sold at these markets, they are distributed to other regions for wider availability. Common commodities sold in Wardha’s markets, as per the Agriculture Marketing Board website, include cotton, wheat (husked), gram, pigeon pea, and soybean.

In Wardha, several talukas have submarkets, which help extend the reach of the APMC system and provide more access for farmers to sell their goods locally. However, many local farmers in Wardha have reported that they often feel they do not receive adequate prices for their produce.

List of APMC markets(as of September 2024)

|

Sr. No |

Name |

Est. Year |

Chairman |

No. of Godowns |

|

1 |

Arvi |

1937 |

Sandip Diliprao Kale |

|

|

2 |

Kharangana |

1980 |

Sandip Diliprao Kale |

|

|

3 |

Rohana |

1979 |

Sandip Diliprao Kale |

|

|

4 |

Ashti (Wardha) |

1975 |

Rajendra Champatrao Khawashi |

|

|

5 |

Karanja |

1981 |

Rajendra Champatrao Khawashi |

|

|

6 |

Talegaon |

1986 |

Rajendra Champatrao Khawashi |

|

|

7 |

Sahur |

1987 |

Rajendra Champatrao Khawashi |

|

|

8 |

Hinganghat |

1940 |

Sudhir Daulatchand Kothari |

|

|

9 |

Vadner |

1980 |

Sudhir Daulatchand Kothari |

|

|

10 |

Kangao |

2021 |

Sudhir Daulatchand Kothari |

|

|

11 |

Pulgaon |

1961 |

Manoj Vasantrao Wasu |

|

|

12 |

Deoli |

1971 |

Manoj Vasantrao Wasu |

|

|

13 |

Samudrapur |

1997 |

Himmat Shamrao Chatur |

|

|

14 |

Mandagoan |

1998 |

Himmat Shamrao Chatur |

|

|

15 |

Sindi |

1942 |

Keshrichand Balaramji Khangare |

|

|

16 |

Wardha |

1939 |

Amit Arunrao Gawande |

|

Farmers Issues

Farmers in the Vidarbha region face significant challenges, with recurring droughts being one of the most pressing. Heatwaves, water scarcity, and famines are common in the area, creating a precarious situation for agricultural livelihoods. The district experienced a severe drought for three consecutive years from 2014 to 2016, exacerbating the hardships faced by the farming community.

A report on the impacts of climate change on drought and its consequences for agriculture under worst-case scenarios over the Godavari River Basin predicts that the central belt, particularly the sub-basins of Wardha, Wainganga, and Pranhita, will experience more frequent drought episodes in the future. These sub-basins, located in the northwestern part of the Godavari River Basin (GRB), are expected to see reduced precipitation, resulting in even drier conditions.

The effects of drought are compounded by several systemic issues: inadequate social support infrastructure at the village and district levels, the inherent uncertainty of agricultural enterprises in the region, farmer indebtedness, rising cultivation costs, falling prices for farm commodities, limited credit availability for small farmers, and the relative lack of irrigation facilities. Together, these factors have contributed to an increase in farmer suicides, as highlighted by a report on farmer suicides in Vidarbha.

P.B. Behere and A.P. Behere (2008), in their research article, mention that the number of claims linked to farmer suicides rose dramatically from 26 in 2003, 29 in 2004, and 26 in 2005 to 154 in 2006 and 128 in 2007. A 2017 news report revealed that between January 2006 and October 2016, 1,313 farmers in the district took their own lives. Furthermore, a 2017 article about a similar issue talks about how the crisis was further aggravated by the exclusion of Wardha from the state’s 2017 loan waiver list, leaving many farmers without critical financial relief.

Graphs

Irrigation

Cropping Metrics

Land Use and Credit

Sources

Anusha. 2017.1,313 farmer suicides in Wardha in 10 years, yet it is not on loan waiver list.OneIndia.https://www.oneindia.com/india/1313-farmer-s…

G Seetharaman. 2016.Third year of drought in Wardha, Vidarbha. Economic Times.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/po…

Govt. Of Maharashtra. 1974. District Gazetteers, Wardha District. Gazetteers Dept. Mumbai

Gsda.maharashtra.gov.in.Wardha.https://gsda.maharashtra.gov.in/en-wardha-di…

Khagendra P. Bharambe, Yoshihisa Shimizu, S .A. Kantoush, T. Sumi. M. Saber. 2023. Impacts of climate change on drought and its consequences on the agricultural crop under worst-case scenario over the Godavari River Basin, India. Vol. 32.Climate Services.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Maharashtra.gov.in.Wardhahttps://shorturl.at/3neUx

Msamb.comhttps://www.msamb.com/ApmcDetail/Profile#pag…

NABARD. 2023-24. Potential Linked Credit Plan:Wardha. Maharashtra Regional Office, Pune.

P.B Behere. A.P Behere. 2008. Farmers' suicide in Vidarbha region of Maharashtra state: A myth or reality?. Vol. 50, no. 2.Indian Journal of Psychiatry.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC273…

R. Rukmani & Manjula. M. 2009. Designing Rural Technology Delivery Systems for Mitigating Agricultural Distress: A study of Wardha District.M S Swaminathan Research Foundation Chennai.http://59.160.153.188/library/sites/default/…

R.V Russel. 1906.Central Provinces District Gazetteer: Wardha District, Vol A, Descriptive. Pioneer Press. Allahabad.

Yukta Mudgal. 2024.Be Stubborn Enough to Learn Something New: Maharashtra’s First Drone Didi. Krishi Jagran.https://shorturl.at/xUgEK

Last updated on 6 November 2025. Help us improve the information on this page by clicking on suggest edits or writing to us.